What I learnt from reading 100+ political economy papers:

My biggest takeaways

This year, I took courses in political economy and economic history as part of my master’s in economics. These involved a lot of reading. I read around 80 papers in political economy and 80 papers in economic history, each around 40 to 50 pages long. Since there’s overlap, let’s call it over 100 papers. That was a lot of material, and though I haven’t covered every single possible topic, I definitely read both broadly and deeply.

Having finished my exams yesterday,1 I now sit here with the mostly pointless skill of being able to summarise in a lot of detail every single one of the papers I read. And while I can still do that, I thought it would be a good idea to summarise the insights that this literature has given me. These insights range from empirical findings that I didn’t know were true, to technical points about econometrics and even some arguments that changed how I think about the field of economics as a whole.

Below are 10 of the most interesting things I learnt, and some ramblings to go with them. If you don’t want to read the explainers, here is the list:

Colonialism changed everything

We may never know what caused the great divergence because we don’t have the right type of data

Institutions are part of the story

There is a disconnect between growth pursuing policies in developed countries and the origins of growth literature.

Variation in priors necessarily imply heterogeneous treatment effects

Writing a paper for a top economics journal in 1945 was like writing a long essay; in 2025 it’s more like directing a movie

Exogeneity is overrated

State capacity plus political limitation is the best theory of institutions

Central Africa is different

Religion and political ideology are deeply held beliefs that can be demonstrated by revealed preferences

The reversal of fortunes story does not apply to Africa

Colonialism changed everything

On my first reading of the literature on the origins of growth, I was very surprised by how many of the causes of growth can be ultimately traced to colonialism. Whether through the formation of extractive or inclusive institutions (Sokoloff and Engerman, 2000; Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, 2001; Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, 2002), importing human capital (Glaeser et al, 2004), spreading common or civil law around the world (LaPorta et. al, 2009), preventing state formation by disempowering local elites (Dell, 2010; Dell et. al, 2018), or by destroying social cohesion and trust through slavery (Nunn, 2008; Nunn and Wantchekon, 2011), colonialism was an enormous shock which changed the course of history for the colonised countries.

We may never know what caused the Great Divergence because we don’t have the right type of data

One of the most important open question in economics is why there is such an enormous gap between the living standards of the world’s richest and poorest countries. This is a big question—a macro question. Unfortunately, empirical economics is generally not so good at answering big questions. It is pretty good at answering small questions: how did a particular policy affect a particular group of individuals at a particular time and so on. For these questions, economists can get massive sample sizes since the unit of analysis is individuals, of which there are 8 billion to choose from. They can also conduct experiments—randomly giving different people policies in a controlled environment where other things are held constant.

For macro questions, the same type of study is not possible. There are less than 200 countries in the world and the Great Divergence only happened once. Economists can’t conduct experiments where they randomly assign some countries 100 years of communism or colonial rule or tropical diseases.

But economists really want to answer big questions and so they resort to two second best options. In an attempt to answer big questions, economists either study individual level variation and hope it extrapolates to big questions2, or they study small sample cross-country regressions and aim to explain the variation in cross-country wealth directly.3

The problem with the micro approach is that we can never be sure that context-specific individual level variation extrapolates to explaining why an entire country is different from another. The problem with the macro cross-country approach is that causal effects are hard to identify in this case: regardless of identification strategy, causal effects in a cross-country regression are identified by the drastic assumption that an entire country can be considered a counterfactual for another. Even with a compelling causal argument, these claims are hard to justify.

Thus, when it comes to big questions in economics, like why the great divergence happened, we have imperfect data in either case. As I have said before, there is trade-off between identification and the importance of a conclusion. Until aliens take control of earth and perform a balanced RCT on two random samples of countries, then no economist will ever be certain about why some countries are richer than others.

Institutions are part of the story

Having just stated that we can never be sure why one country is richer than another, I still think that there is one thing that we can be quite sure of: institutions matter. The reason why I think this is because of the explanatory power that institutions offer. East and West Germany, North and South Korea, Mexico and Arizona and so many other examples4 tell us that geography or human capital can’t be the only things creating vast differences in economic outcomes across the world. If you take any pair of countries in the world with a large difference in income and try to explain the difference using variation in institutions, you will probably get somewhere.

I think there is an analogy to be made between institutions explaining economic development and evolution explaining species variation. Though neither theory can be tested on the grand scale that we would like—we can’t watch single cells evolve into humans in a lab and we can’t observe random variation in institutions across countries—explanatory power alone is enough to make both theories credible. Evolution almost always works as an explanation for why an organism has a particular trait and institutions almost always work as an explanation for variation in economic outcomes.

In my opinion, the task of modern political economists is not answering whether institutions matter, it is answering the many questions that this conclusion raises. For instance, what even are institutions? Everyone agrees property rights are important, but are they an institution or an effect of institutions? What are the properties of good and bad institutions? Where does variation in institutions come from? How do institutions interact with other variables, like culture?

Though not unanimous, it is largely accepted that institutions are really important for economic growth and as a result, political economists have moved on to new questions like those above.

There is a disconnect between growth pursuing policies in developed countries and the origins of growth literature

I live in the UK, a country which has struggled to achieve any noticeable economic growth since the financial crisis. Underinvestment, immigration and Brexit are often cited as the reasons why. Much less frequently is it said that the UK’s growth problems can be explained by poor quality institutions. This is despite the fact that institutions are by far the most commonly cited explanation for income differences across the world in the political economy literature.

I think the politics world could do with having a look at this literature. Britain’s housing shortage is often framed as an underinvestment problem—not building enough homes—which is sort of correct, but I think the underlying problem is an institutional failure. Dincecco and Katz, 2014 might argue that the UK has failed to get the balance right between property rights protection and the benefits of occasional use of the coercive power of the state. Dell and Olken, 2020 might argue that, when the coercive power of the state is used to build infrastructure, it can be much better than a stateless alternative where nothing gets done. The idea that we just need to build more homes is accurate but the reason why we never actually do is not because the government can’t afford to or doesn’t want to, it is because institutions are such that it cannot.

That said, institutions are not the only feature of the literature on the origins of growth which is never talked about in political debates. Changing fertility patterns are often seen as a potential cause of North West Europe’s differential growth (Hajnal, 1968) since lower birth rates bring more investment in each individual child (Kremer, 1993; Galor and Weil, 2000) and give more time for women to work. Another culture shift seems to have occurred in the past 20 years such that average birth rates in many developed countries are now below replacement. Again, this is rarely brought up as a matter of political interest and yet it is commonplace to find discussions of cultural attitudes towards fertility patterns in the literature on economic growth around the world.

Variation in priors necessarily imply heterogeneous treatment effects

This is a technical point for my econometrics friends. Let’s say I randomly assign a treatment in an experimental setting. The treatment updates the beliefs of participants about something. For some, it updates their beliefs upwards. For others, downwards. In other words, some treated participants have a positive treatment effect while others have a negative treatment effect. These two forces may cancel each other out and present as no treatment effect if I were to only look at average treatment effects and ignore heterogeneity.

It’s probably easiest to explain using the example in Cantoni et. al (2019). In a randomised experiment, participants at Hong Kong University were asked to guess the percentage of their classmates that they thought would participate in a scheduled protest. Participants were also asked whether they would protest themselves, allowing the experimenters to get an estimate of the true number of protestors. The experimenters then told a randomly assigned treatment group the true expected number of protestors, allowing the treated group to update up or down. On average, out of a sample of 2000, people correctly guessed the number of participants. Thus, the average treatment effect in the experiment was zero. However, the purpose of the study was about whether students were more likely to protest themselves when they underestimated the true number of protestors (and were told the true number allowing them to update up) or when they overestimated the true number (and were told the true number allowing them to update down). Without specifically analysing heterogeneity among the treated group, these effects could have been completely missed. Thankfully, since the experimenters knew their paper was about belief correction, and expected both upward and downward updating, they anticipated these heterogeneous treatment effects.

For another paper which studied heterogeneous treatment effects due to upward and downward belief updating, see Burzstyn et. al (2020)

Writing a paper for a top economics journal in 1945 was like writing a long essay. In 2025 it’s more like directing a movie

In 1945, Friedrich Hayek published “The use of Knowledge in Society” in the American Economic Review, one of the most important and influential economics publications of the 20th century5. This article is a 12 page essay, made up of ideas comprised out of thin air from the mind of one of the world’s great thinkers. It has no acknowledgements, no references and only one footnote. I don’t think there is a single number in the essay, let alone a mathematical equation.

Things have changed since 1945. Of the 100+ modern political economy papers I read, virtually every single one had a long list of references, pages of tables and plenty of maths. The most striking difference between old and new economics papers though, is how much bigger modern ones are in scope. Consider Beraja et. al (2023) which collects around 3 million observations of data on procurement contracts issued by the Chinese government, or Sanchez de La Sierra (2020) which used the help of 20 research assistants, or Aneja and Avenancio-Leon (2019): a highly influential working paper which is 98 pages long. In 2025, professors writing in top economics journals are managers of massive projects, often making use of the help of 10 to 20 individuals and building on and referencing the work of thousands of others.

This dramatic shift has made the reading experience different for old and new economics papers, but there is value in reading both. Any economist who knows me well will have heard me rave about Hayek’s old articles from the 1930s and 1940s, and how there is still untapped wisdom in them. But I also think it’s good to have well-identified empirical findings that survive 50-pages of robustness checks too. And empirical papers are not always boring and uncreative. Consider 1984 or Brave New World (Chen and Yang, 2019) which runs a randomised experiment offering free-VPN access to Chinese students allowing them to bypass internet restrictions, testing whether China’s information environment is fundamentally limited by restrictions on supply (IE blocking websites: The 1984 scenario) or a lack of demand for any of the restricted information (The Brave New World scenario). What an exciting paper which is nonetheless long and full of maths and tables and references.

Exogeneity is overrated

Economists love causal effects. They love to be able to say that the relationship between two variables is not just a correlation but a causal relationship. In order to do so, economists often resort to quite drastic measures. They sometimes conduct experiments where one group is randomly assigned into receiving a treatment and another is randomly assigned into a control group. Thanks to the randomisation, the economists conclude that any differences observed between the two groups after treatment must be attributable to the treatment—a causal effect has been uncovered.

However, leaving aside the typical questions of external validity of RCTs, Dal Bo et. al (2010) found another potential critique of RCTs. Exogenously imposed treatment effects might be different to endogenously determined treatment effects, even when the treatment in question is the same. To discover this fact, the experimenters made participants play a repeated prisoner’s dilemma game, where the best response is to defect, before allowing participants to vote on whether to switch to a coordination game, where the best response is to cooperate. A computer would then randomly determine whether to accept the vote (i.e. allow the decision to switch to coordination or not switch to be endogenously determined) or to override the vote (make the decision to switch or not switch be completely random/exogenous). The idea behind this experiment was to test whether participants were more likely to cooperate in the coordination game when their switch in payoffs was known to have been chosen by a vote compared to when their switch was known to be randomly determined.

This is exactly what they found—what they describe as an endogeneity premium—a differential effect of switching to the coordination game when the switch was known to have been determined endogenously.

So why is this lab experiment ground-breaking? That is because most economists always see exogeneity as a first best. They strive to argue that the treatment they study was assigned exogenously. Yet, Dal Bo and co-authors argue that exogenous policies might have different effects on people compared to endogenous policies. For example, in the real world, the fact that many people voted for Brexit might influence the behavioural response to Brexit-related policies. If Brexit were somehow handed to the UK as a natural experiment, it might have had different consequences.

The difference between exogenous and endogenous treatment effects is important because almost every policy in the real world is endogenously determined. Policies don’t come out of nowhere, they are typically a response to some problem which the politician wants to fix, or a response to the fact that a new government has been voted in by the electorate. Yet, while the real world is full of endogeneity, economists only study exogenous treatment effects—they only can identify causal effects when treatment was assigned exogenously. Thus, the random or natural experiments that economists use to draw inference about policy in the real world may have entirely different treatment effects when compared to real-life policies which were implemented as a result of a long chain of endogenous events.

State capacity plus political limitation is the best theory of institutions

Institutions are important for economic growth. Basically everyone in the literature at agrees on that at the moment. The problem is defining what exactly we mean by good institutions. Take the example of property rights. We want good institutions so we can protect property rights. But this requires two contradictory forces. On the one hand, we need a state that is constrained against the arbitrary expropriation of resources (North and Weingast, 1989; Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, 2001; Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson, 2002; Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, 2005) such that people are willing to invest in the long term prosperity of their property without worrying about it being taken away. On the other hand, the state must be granted coercive power and a monopoly on violence in order to protect property rights from non-state actors. (Tilly, 1990; Epstein, 2000; Broadberry, 2021) That is, the government needs to protect your property from robbers or invaders and it needs to be granted coercive power to do so.

Thus, the state needs some coercive power but not too much in order to have good institutions which protect property rights. Sounds strange, but this I believe, is the correct way to think about institutions. The importance of having some but not too much coercive power can also explain things like public good provision. Public goods are socially beneficial, but due to free-rider problems they can only be funded by a large state actor who can collect taxes by force. Then again, the monopoly on violence required to collect taxes and fund public goods can easily be harmful in the hands of corrupt leaders.

Along these lines, Dincecco and Katz, 2014, show that both fiscal centralisation and political limitation are associated with higher economic growth. Crucially though, political limitation only matters when you have fiscal centralisation. Roughly speaking, what that means is that the state needs to be given a monopoly on violence such that it can raise taxes by force to fund state-led activities, but the state must also be constrained politically—constrained against using its power arbitrarily for the personal gain of those in power. It’s also no good constraining the state’s power unless it already has a monopoly on violence such that it can raise taxes. When states are particularly weak, it’s probably better to give them more power, not less.

This theory of institutions which is something like give the state a monopoly on violence so that it can protect property rights and invest in public goods, but make sure the state exercises its power with constraint and consistency is the way that I think about good institutions. Though I’m not entirely convinced by the empirical results of Dincecco and Katz, 2014 I think their idea of how good institutions work is probably right.

Central Africa is different

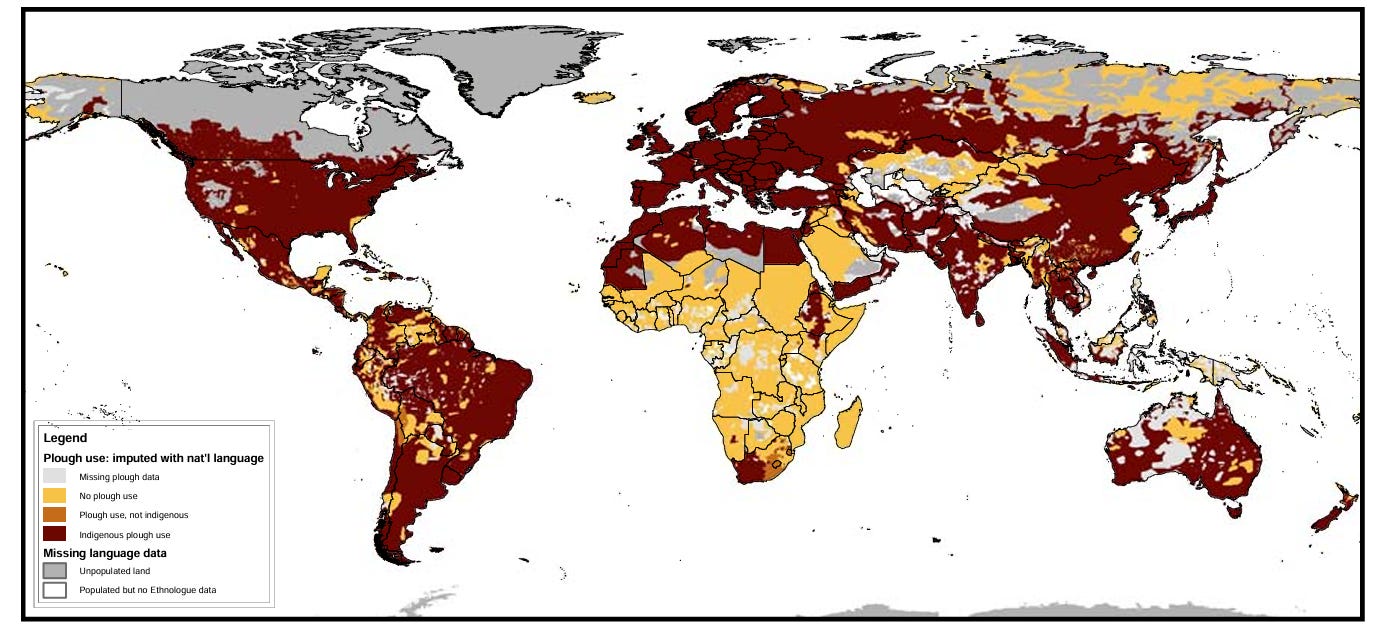

Take a look at this graph from Alesina, Giulano and Nunn (2013), a paper arguing that modern gender inequality can be explained by historical suitability of land to the plough. The map shows suitability for plough agriculture across the world. Notice how most of the variation comes from central Africa.

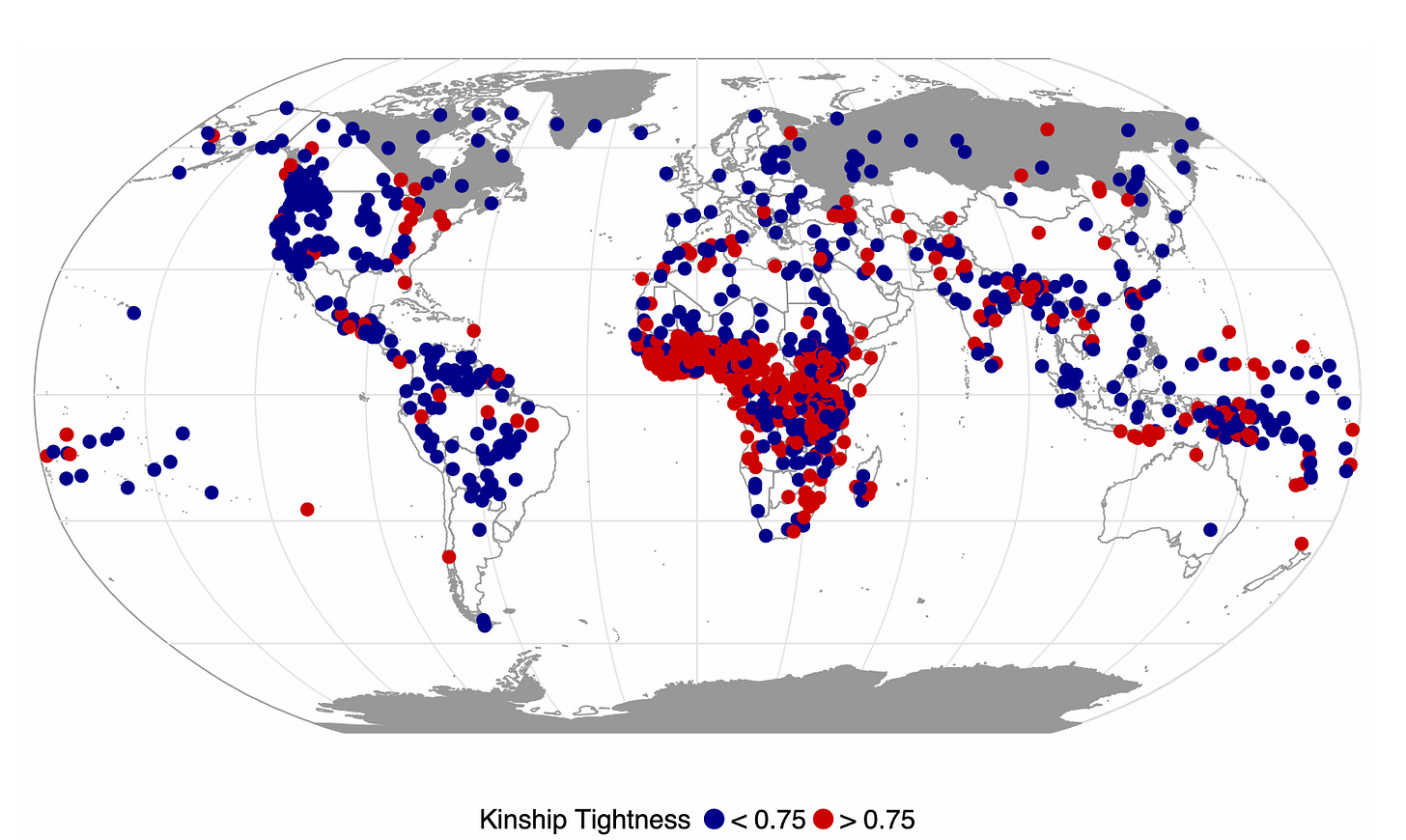

Now take this paper: Enke (2019), which argues that culture and ultimately economic outcomes across countries can be explained by variation in kinship tightness: while Europe consists of tight nuclear families, Africa has much larger family structures and this is associated with lower levels of trust and cooperation with broader society. Again, notice how much of the variation is coming from Central Africa vs the rest of the world.

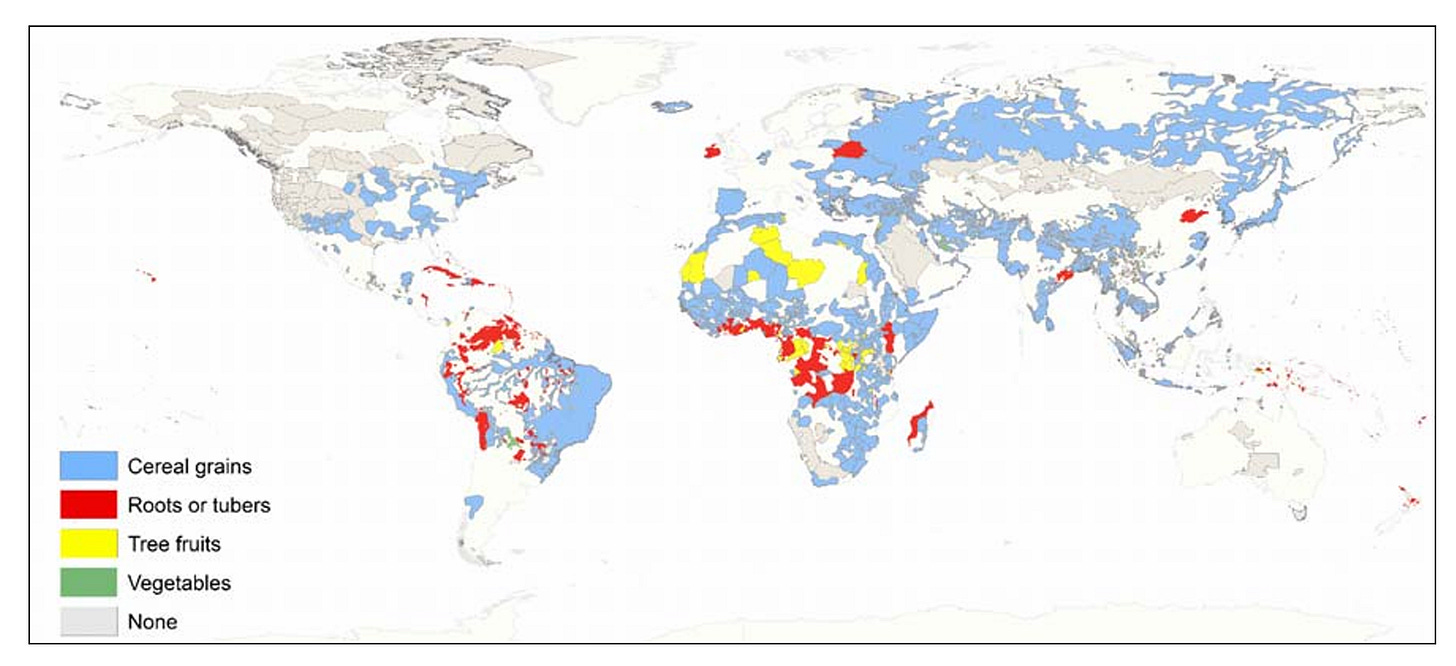

Here is a paper from Mayshar, Pascali and Moav (2013), arguing that historical state formation was possible only in areas with land suitable to grain agriculture, not roots or tubers. Notice how central Africa is the key player here also.

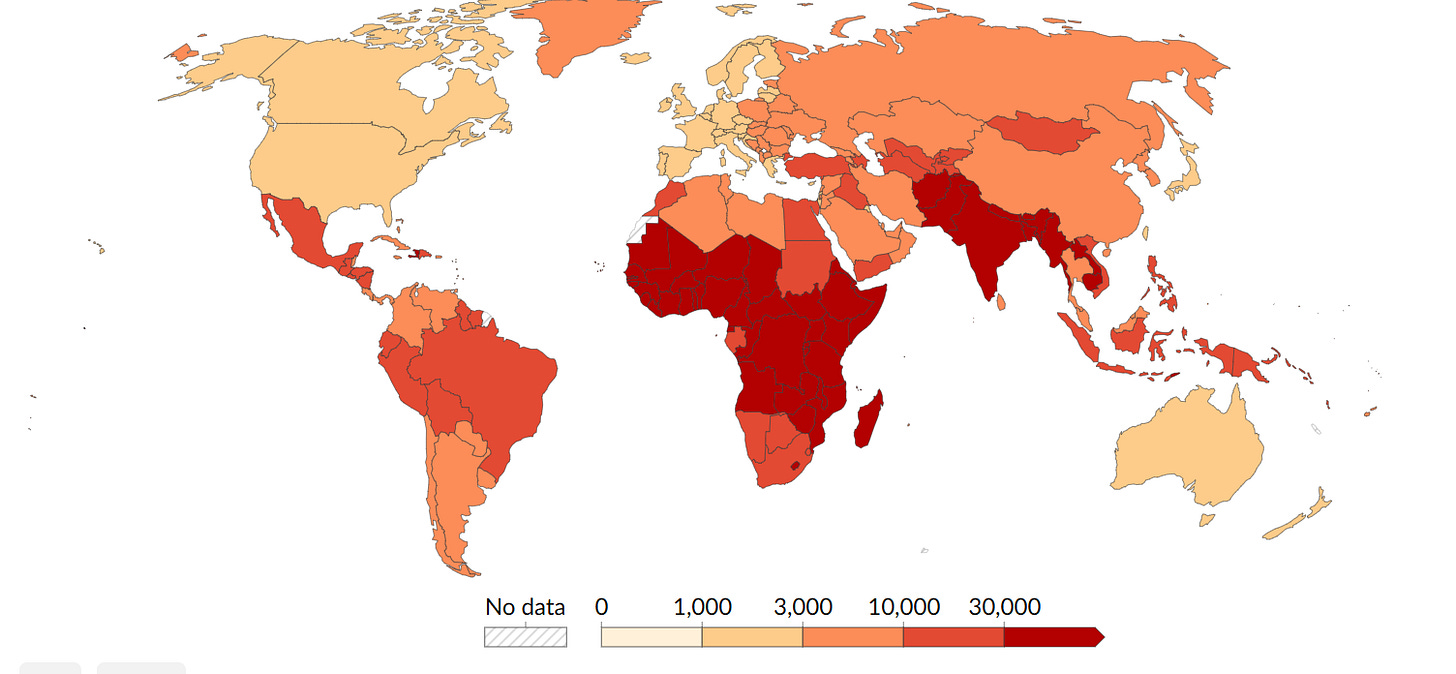

Finally, here is a map of disease burden across the world from communicable diseases, something which on its own is likely to be pretty bad for economic growth, but that also may have interacted with institutional developments during colonialism Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, 2001.

See also, a map of ethnic diversity across Africa where we can see that central Africa is far more ethnically fractionalised than the rest of the continent, something which may in itself have stifled growth due to inter-ethnic conflict (Carlitz et. al, 2024) or through an interaction with the Scramble for Africa, where borders were arbitrarily assigned across ethnic boundaries (Michalopoulos and Pappaioannou, 2016). Finally, see a map of the transatlantic slave trade, again where most of the variation comes from central Africa. The slave trade has also been suggested as a possible cause of poor economic performance in Africa (Nunn, 2008; Nunn and Wantchekon, 2011).

All of this is to say, central Africa is different, on a huge number of dimensions, all of which seem to be negatively associated with economic growth. It’s hardly surprising then that central Africa is the least economically developed region of the world.

This fact makes me pretty confident that we cannot explain away Africa’s underdevelopment by one factor. There are many many reasons why Africa is poor and we should not attach too much weight to one single theory. This idea also potentially explains why figuring out the growth puzzle is so difficult. In the case of central Africa, more than one factor contributed to its underdevelopment and so more than one solution will be needed to get it back on the right track.

Another lesson from these maps is to be sceptical of global cross-country regressions when all of the variation is coming from one location, particularly if that location is central Africa which we know is different for many reasons, some of which are just coincidentally independent.6

Religion and political ideology are deeply held beliefs that can be demonstrated by revealed preferences

People subscribe to all manner of peculiar ideas, often leading them to act in ways that defy traditional economic predictions. Yet, questions remain about how far this irrationality truly extends. Are individuals genuinely prepared to compromise their economic interests simply to protect a belief? For example, if someone asked me who my favourite basketball player is, I’d say Lebron James, but if I were given £1 million to argue that he’s overrated, I’d happily do that too. Does this same logic hold when it comes to deeper convictions, like religious faith or political ideology?

There are 2 great studies we can look to here, with similar but not identical conclusions. When it comes to political beliefs, Burzstyn et. al (2020) studied anti-American ideology among Pakistani men. They used an experiment where they offered participants a free gift of around one fifth of a day’s wages, but the participants had to express gratitude to the US government in order to receive the gift. They found that a significant proportion of participants were willing to forego around one fifth of a day’s wages in order to express anti-American sentiment. However, as that amount increased, the proportion which denied the payment in order to express anti-American ideology decreased. These results support the possibility that political ideology can lead to irrational behaviour which can be observed through revealed preference. However, the results also support something of a downward sloping demand curve for political ideology: as the trade-off between ideology preservation and financial reward increased, individuals were more likely to just go for the money.

And when it comes to political ideology, it isn’t just financial rewards that lead individuals to suppress their beliefs it is also social pressure. The paper by Burzstyn and co-authors also showed that when individuals hold minority political beliefs, they prefer to express those beliefs privately and may be willing to suppress their beliefs when faced with a large public majority against them. Thus, not only can political beliefs be crowded out by financial motives, but also by social pressure to conform to a majority opinion when the political belief is unorthodox.

So political ideology is real but can be suppressed with large financial and social incentives. What about religion? As you might expect, religious beliefs seem to be much more deeply held than political ones. Augenblick et. al (2016) studied a group of individuals who held a specific belief that the world was going to end on the 21st May 2011. The experimenters offered individuals a choice between receiving a payment of $5 now or a much larger payment in 4 weeks, after the expected date of the end of the world. Astonishingly, as the experimenters varied the larger offer, even up to $500, individuals remained absolutely fixed in accepting the $5 today, assuming that the $500 in 4 weeks was worthless since it came after the predicted apocalypse date. In this case, there was no downward sloping demand curve: individuals were simply unwilling to accept any money after what they saw as the certain date of the apocalypse7. Importantly too, the end of the world predictions turned out to be wrong, meaning we have at least one piece of evidence that individuals are willing to hold on to incorrect beliefs even at massive financial cost.

This literature on revealed preferences and beliefs is fascinating but it leaves me with so many questions. Is religion the only type of belief that individuals hold on to at extreme financial penalty? How do we explain the fact that many people have gone to martyrdom defending secular political ideologies (e.g. fighting for one’s country in a war)? Are religious believers maximising their welfare, but simply taking into account the afterlife and promised future rewards? Does social pressure to conform mean that far more people have questionable political beliefs (e.g. conspiracy theories) than we observe in public?

Either way, I wanted to share these papers because I think they’re great.

The reversal of fortunes story does not apply to Africa

In their 2002 paper, "Reversal of Fortune," Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson made a powerful claim that the enormous economic inequality we see across the world today is not a permanent feature. They found that the fortunes of many nations reversed after colonialism, with rich countries becoming poor and poor countries becoming rich. Empirically, AJR showed that economic prosperity before the year 1500 is negatively correlated with prosperity in 1800 and later. This is an optimistic finding because it suggests that global inequality isn't inevitable; rather, it is the result of specific policies that could have been different and might be reversible. A similar argument had been made previously by Sokoloff and Engerman (2000), who observed that countries like the United States and Canada were once much poorer than other parts of the Americas like Mexica, Cuba, Barbados and even Haiti. This situation only reversed after the onset of colonialism.

Unfortunately, a notable exception to the reversal of fortunes rule is Africa which AJR excluded from their sample due to a lack of data. Though evidence is sparse, it is likely true that Africa was poor before 1500 and it is true that Africa is poor now. In fact, unless you go back to Ancient Egypt8, there really never was a time when Africa was a leader in global economic development. For most of history and all of modern history, Africa has been poor in both relative and absolute terms.

This fact is cause to be a bit more pessimistic about economic growth. Like I said in no. 9, central Africa is very different to the rest of the world on many dimensions which cannot really be changed. And as I have just laid out, it also has always been one of the poorest regions of the world. Those two facts are really concerning and suggest that we should be sceptical of predictions that Africa will experience transformative economic growth any time soon.

Honourable mentions:

Some bonus takes that I don’t have time to elaborate on:

The Chinese Great Famine was caused by central planning (Meng et. al, 2015).

State attempts to change culture often fail (Fouka, 2020).

Persistence papers might all be wrong (Conley and Kelly, 2019).

It is not always in the interest of autocracies to pursue censorship of information (Qin et. al, 2017).

Property rights don’t always come from institutions (Hornbeck, 2010).

Politicians can pick winners as long as there is a competition mechanism between politicians (Bai et al., 2019).

Financial incentives don’t crowd out personal motivations for public service. The reason is that people from disadvantaged backgrounds disproportionately have public service motivation but also need money (Dal Bo et al., 2013).

Causal identification in top 5 economics journals after ~2020 is often flawless. The problem with modern papers is external validity, not identification.

Some takes from the more history focused papers which I may never have time to write up in full:

We’ve come a long way. In Britain in the mid 1800s, women had an average of 8 children and an average of 5 survived to childhood.

The Great Divergence started in 1700 (Broadberry, Guan and Li, 2018).

We didn’t know historic GDP figures until extremely recently (Broadberry et. al, 2011; Li and van Zanden, 2012; Broadberry, Guan and Li, 2018).

There were institutional differences between Europe and the rest of the world that can be measured long before the industrial revolution and even before the black death (Blayes and Chaney, 2013; Chaney, 2018).

Any account of historic economic growth needs to account for the fact that poorer economies not only grew less but shrank more (Broadberry, 2021).

Protectionist policies played an enormous part in Britain’s industrial revolution.

And finally, some tips for approaching reading a massive body of literature

Try to read papers as the author’s intended. If it’s in a top journal, then none of the paper is junk. Each section is there for a reason, and you skip sections at your peril.

ChatGPT summaries are good to read before you start a paper, but they are no substitute for reading the paper yourself and making your own summary. I find struggling through every line of a paper is better for my long term memory and understanding than reading a summary.

If you are using ChatGPT to help you understand a paper, present it with a pdf of the paper as an attachment and tell it to read the paper in the prompt. In my experience, it is far less likely to hallucinate things from the paper when you do this.

Reading loads of papers is 100% worth doing if you want to get into research.

Know that it will get easier. The next 10 papers you read will be easier to understand than the first 10. In particular, applied econometrics papers are all pretty similar so once you’re experienced at reading them, you can speed through them pretty quickly and build your knowledge.

You might not always be able to critique a paper. Sometimes the papers are just correct. If they made it into the top economics journals, then they are unlikely to have many weaknesses at all.

Enjoy the process. There is so much genius in the top economics journals, and much of it is underappreciated. It’s a privilege to have access to an endless supply of carefully refined ideas from the world’s best thinkers.

Turns out this post took me about a month to get finished—my exams finished in mid June!

see Cascio and Washington (2014); Aneja and Avenancio Leon (2019); Bernini, Facchini and Testa (2023) which study the effect of black franchisement on economic outcomes, voter representation and wage equality but study variation within a small subset of states and hope that it extrapolates to the broader franchisement of the black population of the US. Alternatively, consider Dell (2010); Dell and Olken (2020) which study the effect of colonialism in very specific contexts, hoping they might explain the broader effects of colonial policies on the world.

see Nunn (2008) which explains contemporary differences in living standards in Africa by the negative impacts of the slave trade, using a sample size of just over 50, or Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2001), who argue that much of the world’s income differences can be explained by differences in the institutions of countries that colonised them. Again, AJR (2001) uses a very small sample size and much of their data is missing and has to be “guessed” by the researchers.

Also using cross-country regressions, see Gorodnichenko and Roland (2017) who explain cross-country income differences with genetic predispositions to individualist culture, or Voigtlander and Voth (2013) who explain income differences in Europe with the frequency of wars in the medieval period.

see Why Nations Fail by Acemoglu and Robinson for a potentially exhaustive list!

Also an article Tyler Cowen described as the best economics article ever written in his book GOAT. I personally am a big fan and have written about it in a previous blog post!

This is not at all a critique at the papers I referenced in this article. Most of them acknowledge that central Africa is different and show robustness to samples which exclude Africa. The results in these papers are probably correct and it is only when you extrapolate their results to explain growth across the world that we should be sceptical due to central Africa’s differences.

Of course, the offers topped out at $500. It is possible that there was some much higher offer that people would have accepted in order to undermine their religious beliefs

Which is also part of North Africa, so not the region with the most extreme underdevelopment in the world (Central Africa)